Editor's Choice

Don't know where to start? The Victorian Popular Culture team at Adam Matthew pick some of their personal highlights from the collection.

Module I: Spiritualism, Sensation and Magic

Module II: Circuses, Sideshows and Freaks

Module III: Music Hall, Theatre and Popular Entertainment

Module IV: Moving Pictures, Optical Entertainments and the Advent of Cinema

Module I: Spiritualism, Sensation and Magic

Martha Fogg

This module explores the links between the explosion of magic as entertainment and the emergence of Spiritualism. The two phenomena often overlapped: table-turning and the ouija board became popular ‘parlour tricks’, while self-confessed conjurors such as Houdini were unwillingly appropriated as psychic mediums.

Here I have chosen two documents which chronicle this dichotomy and offer insights into the way in which Spiritualism was viewed by the media and public of the age.

Faces of the Living Dead; Remembrance Day Messages and Photographs by Estelle Stead

This fascinating pamphlet by Estelle Stead – daughter of Victorian journalist and social campaigner W. T. Stead – offers an insight into the phenomenon of ‘spirit photography’. Spirit photography began in 1861 with William Mumler’s discovery of a ‘ghost’ on a photograph he had taken of himself. From its inception, spirit photography went hand-in-hand with accusations of fakery – Mumler himself was taken to court for fraud in 1872 – but it continued to hold a fascination for Spiritualists. Spirit photography played a vital role in the development of the Spiritualism movement in the 19th and early 20th centuries, being used as evidence by both sceptics and believers. Faces of the Living Dead; Remembrance Day Messages and Photographs is a defence of the work of the well-known British spirit photographer, Ada Deane. The book offers an account of Deane’s most notorious photograph, taken during the silence at the Cenotaph in London on Armistice Day 1922. According to Stead, Deane was following instructions from spirit contacts:

Some days before the 11th of November, 1921, we kept on getting messages from the Other Side about what was to happen on that day. They requested that a photograph should be taken by Mrs. Deane… they told us that they had prepared a group of “Tommies” and “Hearts of Oak Men” (sailors) who had passed on in the Great War, and if only we carried out their directions they had every hope of getting this on to the plate.

This experiment was repeated for several years, with the resulting prints attracting a lot of publicity and a number of ‘recognitions’ – something that the spirits from the ‘Other Side’ clearly intended:

We were told that those on the Other Side were preparing for further Cenotaph pictures, and this time, if they were successful, they asked me to try and give more publicity to the results. “We want you to bring them to the notice of non-Spiritualists,” they said; “those are the people we want to force to take notice”.

However, the experiment was brought to an end when the 1924 cenotaph photograph was the subject of an exposé by the Daily Sketch, in which it was claimed that the faces of the spirits were in fact those of well-known, and living, sportsmen. Stead’s pamphlet strongly counters these claims of fraud, and as evidence she reproduces the cenotaph photographs and other examples of Deane’s spirit photography. These arresting images are a fascinating visual record of Spiritualist beliefs.

Houdini’s History of Magic Scrapbooks – the Spiritualism Scrapbooks

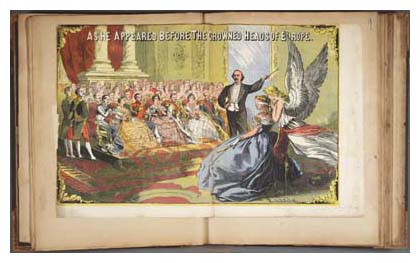

The beautiful History of Magic scrapbooks from the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, are a real treasure of this online collection. They contain clippings, posters, advertisements and much other ephemera relating to both Houdini and other magicians of the age.

The posters in particular are of immense interest, chronicling the important role that magicians’ advertising techniques played in the development of graphic design. The importance of eye-catching visual representations in capturing the attention of the public meant that magicians were among the first to exploit the arrival of chromolithography, which allowed the mass production of colour posters.

The sixth scrapbook, the Spiritualism Scrapbook, contains clippings of articles about the Spiritualism movement, including news coverage of Houdini’s infamous disputes with Arthur Conan Doyle, famous defender of Spiritualism. The men were firm friends, but clashed publicly over Houdini’s crusade to expose fraudulent mediums. Conan Doyle was firmly convinced that Houdini’s campaigns against mediums were the overzealous actions of one who ‘doth protest too much’. In one of these clippings Conan Doyle writes of Houdini:

So far also as he exposes false mediums he is doing the best work for Spiritualism which any man could possibly do. But he himself is in some cases a dupe. It is as easy to be duped by incredulity as by credulity.

What was perhaps still more remarkable was that Doyle ultimately became convinced that Houdini’s remarkable feats of escapology and conjuring could only have been produced by psychic powers – something which Houdini unsurprisingly denied.

Module II: Circuses, Sideshows and Freaks

Martha Fogg

This module contains a fantastic selection of visual material that explores the importance of travelling entertainments in the Victorian and Edwardian periods. Some of the material in this module seems distasteful to our modern sensibilities, but the fascination with freak shows and oddities is a crucial, if unattractive, part of the Victorian psyche. Far more sympathetic is the sheer beauty and grandeur of Victorian fairground art. The two documents I have selected here illustrate both of these elements.

Fairground architecture

Orton and Spooner were British manufacturers of fairground architecture, based in Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire. Victorian Popular Culture includes a large collection of photographs of their work, sourced from the National Fairground Archive at the University of Sheffield. This collection was donated by the family of David Braithwaite, who wrote the seminal history in this area, Fairground Architecture (1968) and intended to write a book on Orton and Spooner, sadly never completed.

The design of the fairground speaks volumes about the democratisation of style and taste during the Victorian period. Although the visual was only one element of the sensory experience that fairground-goers were immersed in, it was perhaps the most crucial in giving the fairground its sense of escape from working life. Fairground art, however garish and overblown, reflected the grandeur and epic scale in which the ‘high art’ of the period indulged. Furthermore, fairground design often reflected wider aesthetic trends – the dragon design seen here is perhaps inspired by the resurgence of ‘chinoiserie’ from the late nineteenth century, a movement itself inspired by the expansion of the British Empire in the Far East during this period.

This ‘galloper’ (the British trade name for the roundabout or carousel) perfectly exemplifies both the taste for the fantastical in fairground art, and the carving skill of craftsmen such as Orton and Spooner. The choice of dragon as the mount reflects the fact that, as gallopers became more sophisticated, the more traditional horses were often accompanied by other animals, both real and imagined (such as pigs, goats, or a cockerel with a man’s head). The skilled carving suggests excitement and movement in the animal (the posture of the legs and the movement of the mouth, even the shining eyes). Altogether, the design is proof of the timeless thrill offered by a ride on the ‘galloper’.

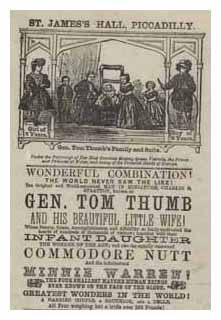

The dwarf ‘General Tom Thumb’ (real name Charles Sherwood Stratton) became one of the most celebrated performers of the nineteenth century under the management of famed impresario P.T Barnum. By the time of his 1863 marriage to Lavinia Warren – a fellow dwarf performer under Barnum’s management – he was a household name and had performed in front of Queen Victoria. The marriage attracted enormous amounts of publicity and was exploited by Barnum in a manner familiar to readers of today’s gossip magazines. The lavish wedding reception was held at the Metropolitan Hotel in New York, and Barnum’s carefully controlled guest list included “a gay assemblage of youth, beauty, wealth, and worth of the metropolis” (Sketch of... General Tom Thumb, 1867). This advertisement for a British appearance of the couple (probably 1865) is a perfect example of Barnum’s genius for hyperbole and willingness to bend the truth in pursuit of spectacle (and ticket sales). To continue the public goodwill generated by their marriage – two years on, presumably now stale news – they are advertised as appearing with “their infant daughter – the wonder of the age” [see the handbill here]. In fact, the couple never had children, and the baby was a foundling. When the deception became difficult to maintain, it was announced that the baby had died (Robert Bogdan, Freak Show, University of Chicago Press, 1990, p.157). This is certainly one hoax that Barnum never mentioned in his Humbugs of the World.

Module III: Music Hall, Theatre and Popular Entertainment

Philippa Hubbard

This section of Victorian Popular Culture explores popular culture from the late Georgian period and throughout the Victorian era. The carefully selected documents convey the range and extent of leisure activities and popular entertainments available to a growing number of people during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I have selected two items from the collection, one of which celebrates an established and popular theatrical form in the Victorian period and another which represents alternative forms of entertainment in late Georgian Britain.

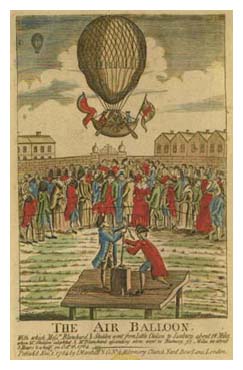

This large portfolio of over four hundred pages comprises engravings, printed advertisements, newspaper clippings, handbills and posters covering various weird and wonderful public spectacles in the late Georgian period. The curious item was compiled by collecting enthusiast Sarah Sophia Banks, sister to the great English botanist Joseph Banks. Sarah Banks made a life out of collecting, amassing everything from coins and advertising cards to admission tickets and bookplates.

This particular scrapbook mainly charts Banks’ curiosity in hot air ballooning, an activity that sparked public interest in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, as the first experimental flights were undertaken in Europe. Print sellers sold images to commemorate these seminal events. The engravings in Banks’ scrapbook mainly document the flights of the Montgolfier brothers, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, and Vincent Lunardi, whose balloon in the colours of the British flag was displayed at the Pantheon in Oxford Street in the 1780s. A print entitled ‘The Battle of the Balloons’ alludes to the intense competition surrounding balloon design and flight in the late eighteenth century.

In the prints, crowds of spectators watch in bewildered awe as balloons ascend the sky. Such public spectacles were alternative forms of entertainment in the late Georgian period. Banks supplemented her collection of pictorial engravings with English and French newspaper clippings and handbills advertising events, new experiments and machinery involving hot air. During the period, exciting advancements in science and technology generated curiosity in public displays, lectures and experimentation.

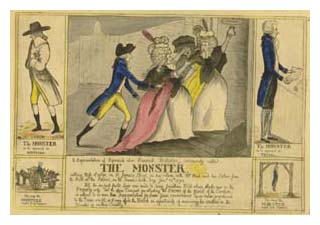

Banks’ collection of ballooning ephemera is followed by a small group of prints depicting human and animal curiosities, and advertisements for Astley’s Amphitheatre, a circus and theatre space. The final set of material tells the story of murderous villain Renwick Williams, dubbed ‘The Monster’ by the contemporary press, who terrorised females in late eighteenth-century London. The well-documented story evidently captured Banks’ imagination and the prints, articles, and advertising ephemera she collated charted Williams’ dastardly deeds, eventual capture and trial in 1790.

Banks’ bizarre scrapbook is both fascinating for the rare printed material it contains and as an item of great personal significance. In devising her scrapbook, Banks created her own form of entertainment by ordering narratives on wonderful, absurd and sinister subjects that captured her imagination. While the portfolio represents only one woman’s private interests, it suggests the many alternative forms of entertainment on offer in late Georgian Britain.

Aladdin; Or, The Wonderful Lamp (1826)

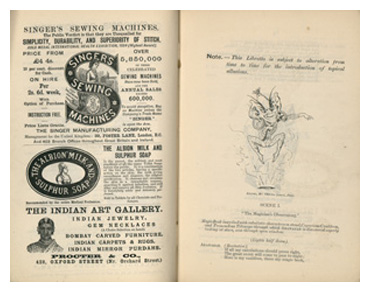

This item is one of 143 pantomime scripts and programmes belonging to the Harry Ransom Centre, Austin Texas. The collection, dating from the late eighteenth century to the turn of the twentieth century, attests to the popularity of pantomime during this period. This particular item (left), published by John Cumberland in 1826, is the earliest script in the collection for Aladdin, a frequently performed pantomime throughout the nineteenth century. The object is not only interesting as an early Aladdin script but is significant as a purchasable commodity related to the theatre. More generally, the collection is suggestive of the increasing commercialisation of the theatre, which emerged in response to the growing popularity of the theatre in nineteenth-century Britain. Cumberland’s early edition described the story as ‘a Grand Romantic Spectacle’, a ‘Magnificent Melodrama’, and offered readers stage directions, a cast list and script, alongside ‘Remarks, Biographical and Critical’. The front cover, embellished with a ‘fine engraving from a drawing taken in the Theatre by Mr. R. Cruikshank’, depicts two serious theatrical characters surrounded by the names of historically important playwrights, including Milton, Sheridan and Shakespeare. In contrast, later editions frequently presented the script alongside comic images of the characters and advertisements for an array of commercial products, often bound within a brightly coloured or heavily illustrated cover. The image below, taken from a programme for a later production of Aladdin in 1885-6, shows a character from Scene One next to a page of advertisements.

During the Victorian period, theatre of all types, both legitimate and illegitimate, became increasingly popular. Pantomimes began to target the middle classes and were written with a family audience in mind. The opening ‘Remarks’ in Cumberland’s Aladdin referred to the expectant crowds outside the Covent Garden Theatre, eagerly awaiting the opening of the theatre doors and the commencement of the production. Items such as printed scripts and programmes, produced for public consumption, reflected a diverse audience, who demanded more colour, sound and spectacle from the theatre. While in 1826, Cumberland’s script boasted descriptions of the cast with their costumes and stage positions, later editions described ‘new and elaborate scenery’, ‘incidental music’ and ‘mechanical effects’. The comedic spectacle of some later pantomimes was also suggested by the increasingly humorous and elaborate titles.

The individual pantomime scripts and programmes in the collection are not only of great commemorative value for particular pantomimes, but as a set they offer a window onto the changing nature and form of pantomime throughout the Victorian period.

Module IV: Moving Pictures, Optical Entertainments and the Advent of Cinema

Lauren Jones

Part IV of Victorian Popular Culture expands upon the existing sections in its exploration of popular culture but goes one, two and even three steps further by offering: a 360-degree object viewer for a selection of optical entertainment artefacts, original film footage from the BFI National Archive and an online virtual exhibition. Given the huge range of material in Moving Pictures, Optical Entertainments, and the Advent of Cinema alone, selecting just a few highlights was a challenge!

This video clip of the kinora is taken from our online exhibition, Optical Delights. Including a selection of these optical entertainment devices in action really makes it possible to imagine the enjoyment and delight of Victorian consumers who were able to make images move for the first time. This section of the exhibition, Kinoras, Flick-books and Mutoscopes, emphasises how the creative seed for capturing moving pictures was planted by the inventors of these early optical (or philosophical) toys. It is perhaps not surprising then that pioneering filmmakers Auguste and Louis Lumière stumbled across their own version of the moving image toy. Patented in 1896, (interestingly a year after their very first film screening of Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon), the kinora was a domestic apparatus derived from the already popular mutoscope; a large-scale mechanical flick-book present in many penny arcades.

This video clip of the kinora is taken from our online exhibition, Optical Delights. Including a selection of these optical entertainment devices in action really makes it possible to imagine the enjoyment and delight of Victorian consumers who were able to make images move for the first time. This section of the exhibition, Kinoras, Flick-books and Mutoscopes, emphasises how the creative seed for capturing moving pictures was planted by the inventors of these early optical (or philosophical) toys. It is perhaps not surprising then that pioneering filmmakers Auguste and Louis Lumière stumbled across their own version of the moving image toy. Patented in 1896, (interestingly a year after their very first film screening of Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon), the kinora was a domestic apparatus derived from the already popular mutoscope; a large-scale mechanical flick-book present in many penny arcades.

The charming sequence featured on this kinora (dated 1911-1914) really made me smile; you can’t help but feel for the persistent zookeeper as he struggles to get the disinterested camel to move for the photographer only to be upstaged by two mischievous zebras who effortlessly steal the limelight! Click on the image to see the clip in full.

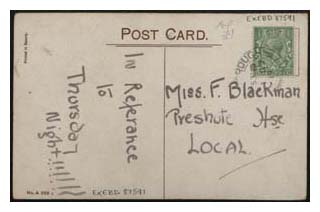

Early Cinema Postcards

The vast collection of postcards featured in Moving Pictures, Optical Entertainments and the Advent of Cinema are absolutely fascinating. At face value they provide evidence of the widespread phenomenon of ‘celebrity’ birthed by the early film industry; every major (and minor) film star of the early 20th century featured on a postcard. Our collection includes everyone from ‘United Artists’ Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks to Hollywood legends Rudolph Valentino, Pearl White and Clara Bow. Production companies such as Pathé Frères, Trans-Atlantic Film Co., Ltd., Goldwyn Studios and American Biograph used postcards as publicity for both films and their stars. Issuing them in ‘series’ form obtainable from cinema publications such as Pictures, Cinemagazine-Edition and Picturegoer made them instantly collectable for film fans who sought to own the entire range.

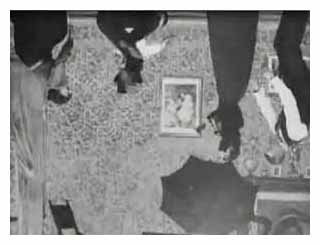

Upside Down; or The Human Flies (1899)

I can’t let this opportunity go by without drawing attention to our specially-selected collection of original film footage sourced from the BFI National Archive. I have always been mesmerised by the allure and magic of the early film era; the palpable excitement that audiences must have felt when watching pictures in animation for the first time and also the terror and bewilderment they would have experienced when witnessing often alarming ‘special effects’ through this new large-scale medium. In this genre, my personal favourite clip has to be, Upside Down; Or The Human Flies (1899). In this clip, a magician waves his wand and makes a top hat fly to the ceiling. He then asks some people to stand before disappearing himself, and then suddenly the remaining people find themselves standing upside-down on the ceiling. What is in fact a very simple illusion – filming with the camera turned upside-down so that the actors appear to be performing on the ceiling – would have been literally astonishing for the film’s contemporary audiences at the turn of the century and that is why, for me, the magic remains so potent.